SOPHIE ERLUND: Destined to Protect the productive, 2021

PSM, Berlin

SOPHIE ERLUND: Destined to Protect the productive, 2021

PSM, Berlin

Photo: Marjorie Brunet Plaza

featuring works:

Parliament of entities, 2021

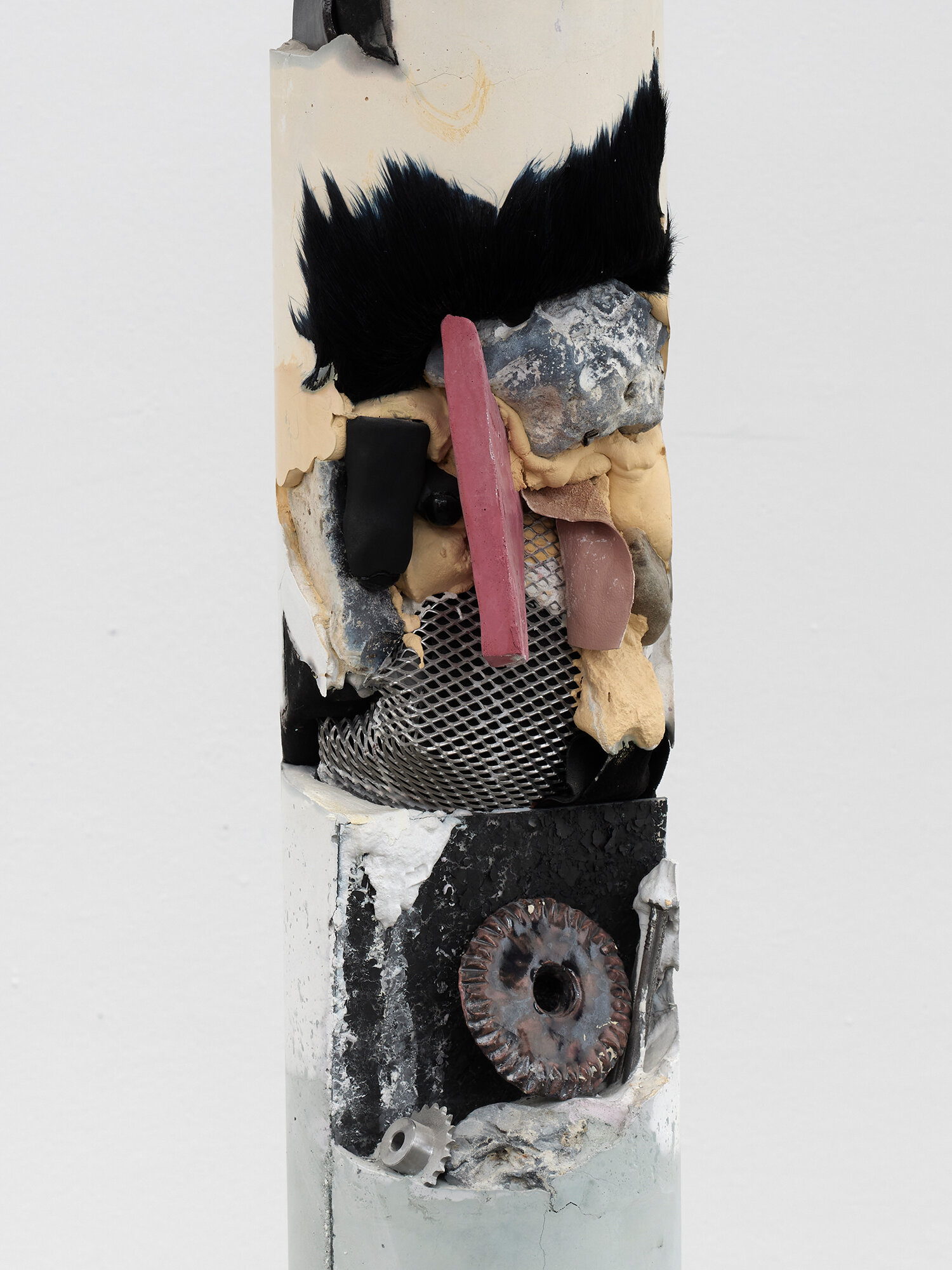

core sample from the technosphere I-IX, 2020-2021

gentle interdependence 1, 2021

gentle interdependence 2, 2021

Symbiotic persona, 2020

As the doors of society begin to creak open once again, we encounter one another with a transformed—indeed traumatic—awareness of who and what circulate through national borders, transportation infrastructure, architectural spaces, air vents and locks. Ours is now an explicitly more-than-human society, in which our relation to other beings is registered on our faces: masks declare recognition of the omnipresence of this Other—and implicitly, of a panoply of others and their various modes of existence. A single viral being emerges from the havoc wreaked on ecosystems and the frenzy of capital circulation that is capable of taking advantage of the global ecological niche that we have constructed. And as much as our fleshy bodies, our heavy metallic infrastructure is vulnerable to its effects. The entanglement of the biotic with the technological realm is a central concern of Sophie Erlund’s solo exhibition Destined to Protect the Productive, a title drawn from a passage of Hannah Arendt’s The Human Condition in which Arendt meditates on the question of who participates in or is served by the political realm. The domain of the political has always been configured in and through structures of economy which enfranchise some at the expense of others—from ancient hierarchies of production and exchange to capitalism’s innovation of alienating labor from the individual who performs it, thus leveling (at least in principle) the field of who might attain the status of a political subject. With this exhibition, Erlund presses the issue of political participation beyond the human, into a domain of ambiguity as disconcerting as it is seductive. Four multimedia compositions comprise the show, marking out different approaches to a central problematic. Its rhetorical centerpiece, entitled Parliament of Entities, consists of a collection of clay sculptural objects arrayed in a circle around a central tower—figures which also feature in an animated video collage by the same title. The objects display naturalistic and partially recognizable biological forms–bits of fur, the semblance of a leaf, or a hominid foot. Some seem to creep or crawl along the floor by virtue of some unfamiliar mechanism of locomotion, while others struggle to hold themselves erect, resisting an impulse to spread out into a smear or a blob. Glazed in earth tones, and metallics, they bear an uncanny resemblance to living entities. This aura of closeness conveys undertones of disgust or aversion—an anxiety to set the elements of this variable sculptural assembly in their rightful place. This desire is answered by an ominous chrome vessel set atop the central tower, poised to decant ceremonial libations, perhaps, or to cast surveillance camera’s gaze upon on the collection of figures below. Erlund’s title invokes Bruno Latour’s idea of the Parliament of Things—a manifesto for imagining modes of political discourse that would extend beyond the human. If our capacities for listening were adequate, Latour urges, then we would be able to attend the subaltern voices, agencies, and agendas of a myriad of things with which we share a world. Erlund’s sculptural manifestation of this idea plays on the double meaning of the term: manifestation as epistemic demonstration and as political protest. In the eponymous video work, one witnesses the animated progression of the sculptural avatars as they swim and slither towards a point of assembly through carefully cropped fragments of our built environment (doorways, staircases, canals). Converging on the tower like dignitaries arriving at a United Nations meeting, stalked by paparazzi and inquisitive journalists, they inspire curiosity about their strategic agendas and alien modes of encounter. The final scenes of the video situate the Parliament of Entities within a broader context—a celestial perspective at once archaic and techno-futurist in its aesthetic. From the aerial view of a god or a satellite hovering above the scene, the assembly assumes the shape of a sundial, suggesting that in the geometric balance of time, each manner of being will receive its moment in the light. Approaching the material legacies of postindustrial culture from another angle, an adjacent gallery, Core Samples from the Technosphere Series. A set of pillars cast in appealing shades of pink, lavender, and green concrete, black, organic, and metallic elements, upon closer inspection these objects are composites of human detritus—gears, fur, bits of computer hardware, electronics and industrial residues. These candy colored monuments are offered as speculative soil-cores of the Anthropocene: evidence of gross overaccumulation and rapid deposition. Their cute pastel colors cast into sharp relief the horror inspired by of the variety and overabundance of source materials—one senses the freshness of a landfill that has not yet had time to compost and sediment, much less to be recycled into newly productive matter. Two framed mixed media collages deepen our speculation of what might become of the entanglement of biotic and technological elements over time. Gentle interdependence 2 presents a composite of computer parts and seemingly organic elements such as mushrooms and wood assembled into a system. One cannot be sure whether it is an electronic device gone feral by coopting the network mechanisms of fungal communication, or whether the biotic elements are busy metabolizing our technological ruins. Gentle interdependence 1 offers a more ominous possibility, incorporating gears and chains into what appear to be the intimate biological space of flesh and cellular structures—an image resonant with the artist’s interest in surveillance capitalism’s penetration into the most intimate realms of life. The vitrines encapsulate alternative visions of possible futures in which the breakdown of distinctions between the digital, mechanical, and biotic have been achieved to strange and disturbing effect. Finally, looking on at a distance from these scenes stand a pair of Symbiotic persona fashioned from machine chains integrated into stumps of wood. These rough, handmade objects, like the exhibition as a whole, traffics in tensions between aesthetics of the primitive and the high-tech, reiterating the question of whether the incorporation of the technical into the biotic constitutes a sublimation, a takeover, or a mutually driven metamorphosis. Over one year has passed since Bruno Latour proposed that the pandemic be viewed a “dress rehearsal” for the disruptions of climate change and the future habitability of our planet for human and other life forms. Viewing Erlund’s exhibition through the motif of the dress rehearsal, the theatrical character of the sculptural ensemble and its video performance comes to the fore. In contrast to the ultimate staging of a play, the dress rehearsal aims to expose failure even as it gestures towards an ideal. Who is missing from the cast? Where is the potential for breakdown within the system? And to what ends might these vulnerabilities be exploited? Indeed, one can well imagine that Erlund’s sculptures come and go, or move around at night, reassembling over the course of the exhibition with different political affordances and insights.

Text: Dehlia Hannah Dehlia Hannah, Ph.D. is philosopher and curator, currently postdoctoral fellow of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts and ARKEN Museum of Modern Art in Copenhagen, where she leads the project Rewilding the Museum (2021-25).